Pappy sure was happy that he was free. Mammy she shout for joy and say her prayers were answered.

-Fannie Moore, born in slavery on Walnut Grove Plantation, South Carolina, 1849

Fannie Moore’s father, Stephen, was a blacksmith. Her mother, Rachael, worked in the fields by day and sewed by night. “Sometimes I never go to bed,” Moore explained. “Had to hold the light for her to see by. . . . I never see how my mammy stand such hard work.” Freedom came as a blessing.

Moore’s recollections, documented in 1937 as part of the Federal Writers’ Project “slave narrative” endeavor, offer a remarkable window into the experience of slavery and freedom in the Carolina Piedmont in the years surrounding the Civil War. She told of parents who stood up for their children, of cruel and kind enslavers, of hard work, dances, whippings, singing, prayer, and death. She recalled the arrival of Union troops, and of the Ku Klux Klan. This Juneteenth weekend, you might spend some time with her stories, including this account of her mother’s suffering and strength.

The old overseer he hate my mammy, cause she fight him for beating her children Why she get more whippings for that than anything else. She had twelve children . . . Every night she pray for the Lord to get her and her children out of the place. One day she plowing in the cotton field. All sudden like she let out a big yell. Then she started singing and ashouting and awhooping and ahollering. Then it seem she plow all the all the harder. When she come home, Marse Jim’s mammy say: “What all that going on in the field? You think we send you out there just to whoop and yell? No siree, we put you out there to work and you sure better work, else we get the overseer to cowhide your old black back.” My mammy just grin all over her black wrinkled face and say: “I’s saved. The Lord done tell me I’s saved. Now I know the Lord will show me the way, I ain’t going to grieve no more. No matter how much you all done beat me and my children the Lord will show me the way. And some day we never be slaves.” Old granny Moore grab the cowhide and slash mammy cross the back but mammy never yell. She just go back to the field a singing.

Moore’s full account is available here (Note: Writers’ Project interviewers generally recorded peoples’ words in conventional dialect spelling; I have chosen not to reproduce that in the quotes I use.)

Moore’s experiences paralleled those of many Blacks enslaved in Mecklenburg County. Charles and Mary Moore, the couple who established Walnut Grove, were part of the same wave of Scotch-Irish Presbyterians who settled Mecklenburg County. They spent time in neighboring Anson County before settling in South Carolina, and maintained close ties to the area. Moore grandson Thomas J. Moore married Mary Irwin, whose father, John, was one of Charlotte’s most prominent bankers and merchants, as well as the owner of plantations in Alabama and Mississippi.

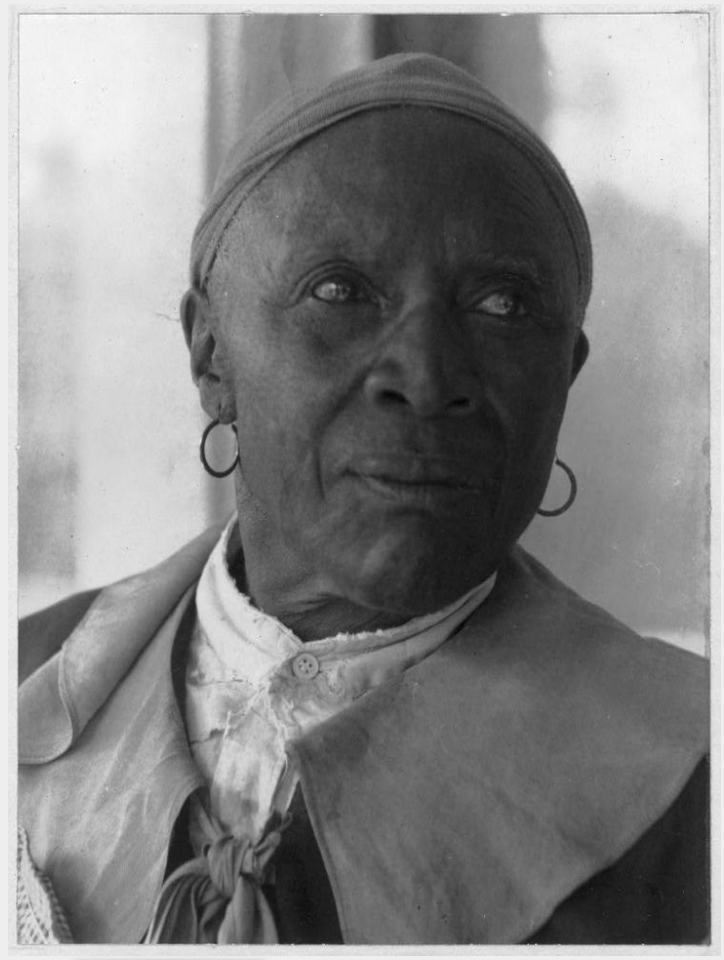

Carey Freeman and Eliza Washington.

The Writers’ Project interview with the most direct bearing on Mecklenburg County took place in Little Rock, Arkansas. Eliza Washington, born in slavery in the late 1850s, told the story of her mother, Carey Freeman, who she noted “was born in North Carolina in Mecklenburg County.”

Freeman’s story highlights a different aspect of life under slavery in North Carolina – the family separations that became especially common as North Carolina slaveholders sought to expand their fortunes by extending their operations to lands recently seized from Native Americans in Tennessee, Alabama, Florida and Mississippi.

Fannie Moore recalled the terror these new economic endeavors brought to enslaved communities. “It was a terrible sight to see the speculators come to the plantation. They would go through the fields and buy the slaves they wanted . . . When the speculator come all the slaves start ashaking. No one know who is agoing.”

Freeman was taken out of Mecklenburg County in the mid 1830s, when enslaver William McNeely moved his family to Tennessee. Eliza was born in Tennessee, and then “the white folks separated my mother and father when I was a little baby in their arms.” Carey and Eliza were taken from Tennessee to Arkansas by one of McNeely’s sons. Eliza’s father, enslaved by another man, was left behind. After the Civil War ended, Carey lived with Eliza and her family in Little Rock until she passed away in 1903.

Eliza’s full story is available here.

Juneteenth was indeed a day for celebration.