“A Position of Respect”

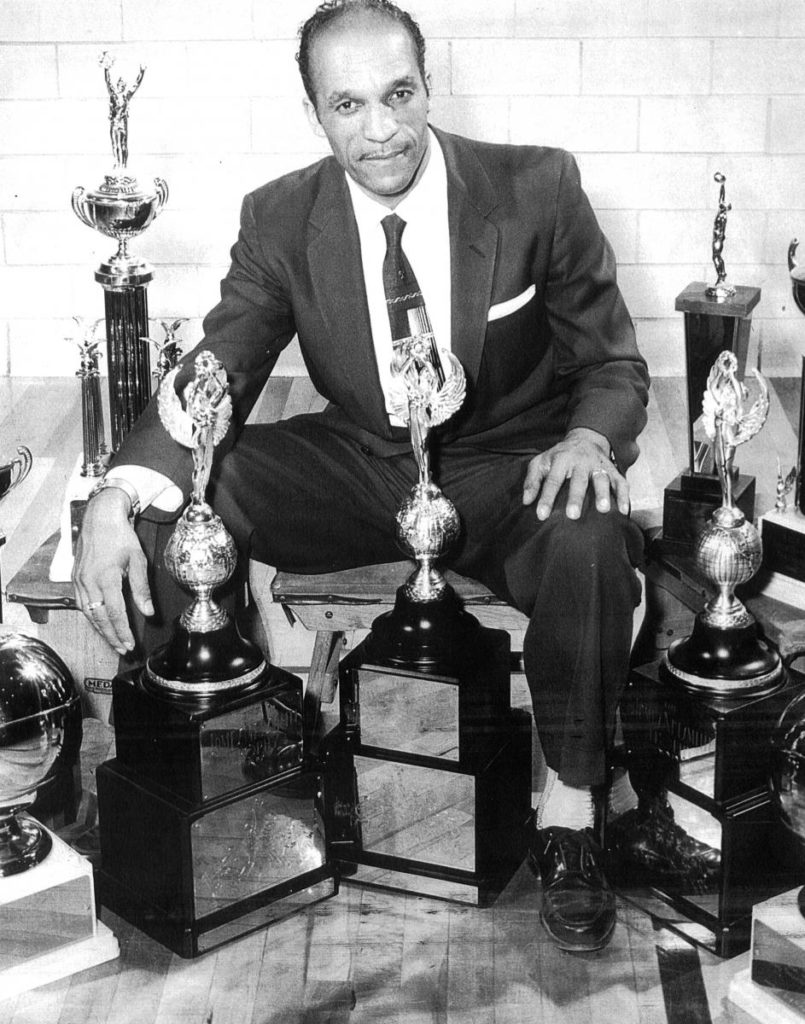

Every February I spend time thinking about Coach John McLendon, one of the greatest basketball coaches of the twentieth century, and one of the most remarkable men I’ve ever met.

McLendon studied physical education at the University of Kansas, where his mentor was none other than basketball inventor James Naismith (I still find it hard to believe that I’ve known someone who knew Naismith). He became the basketball coach at North Carolina College in Durham in 1937, and transformed basketball in the Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association. His accomplishments included pioneering an incisive, fast break style, helping to create the CIAA tournament, and vigorously promoting CIAA talent, including legendary players Earl Lloyd and Sam Jones.

He eventually moved to Tennessee State, where he coached the 1957 team to that year’s NAIA championship, making them the first team from a historically black school to win an integrated national championship. The Tigers won the tournament the next two years as well – a “three-peat” of which McLendon was extremely proud (see photo above).

In 1982, after a long string of coaching accomplishments and groundbreaking efforts to foster athletic integration, he was elected to the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame.

In the following account, McLendon describes the kind of day-to-day negotiations required of African Americans living under Jim Crow, as they sought to walk the fine line between maintaining individual dignity and provoking violent reaction. Like many coaches of his generation, McLendon became a master of such techniques, teaching his players discipline and strategy that stretched well beyond the games they played.

McLendon, who passed away in the fall of 1999, maintained undimmed energy to the end of his life. He sat down for this interview in February of 1998, in the midst of a whirlwind of activity at the CIAA tournament being held in Winston-Salem, N.C. Undistracted by the bustle going on around him, he recalled his long career with zeal, telling stories, detailing his multifaceted coaching philosophy, and describing his many efforts to use sports to promote African American achievement and racial understanding. The full interview from which this excerpt is taken is available in the archives of the Southern Oral History Program at UNC Chapel Hill. You can learn about McLendon in Learning to Win, my book on North Carolina sports, Breaking Through, a biography by Milton Katz, and The Secret Game, a work by Scott Ellsworth that tells the story of an undercover game McLendon arranged between N.C. Central and a powerful Duke team in the fall of 1943.

I put this part of McLendon’s story into poetic transcription, a style developed by scholars in folklore and linguistics. At certain moments in oral interviews, narrators will leave off normal conversation and move into another realm of speech, recounting artfully shaped stories marked by rhythm, repetition, and other techniques of oral storytelling. Presenting these accounts in poem-like form highlights such patterns, invoking the experience of listening to the words.

With the exception of a brief excision near the beginning, the story stands as McLendon told it, word for word. You can listen to it here.